“It’s the economy, stupid!”

That mantra is making a comeback following its heyday when gas prices were well under $1 per gallon. Unprecedented times, in fact, mean that slogan is back in an unprecedented way—but perhaps it should be phrased without the ‘the’: “It’s economy, stupid!”

Today, federal budget dollars are tight, tough decisions need to be made, and investment in energy security appears to be in the crosshairs. We seem to have come back to a politically charged argument from Economics 101: the guns and butter problem. However, in this case the calculus is a wee bit more challenging because there’s a third complementary variable—energy!

As I mentioned in our book’s national security chapter, the Department of Defense’s mission is defense, and energy is key vulnerability. This has been acknowledged going back as far as the Nixon Administration but has really become a major policy focus over the last decade. More important than the opinions of us analysts in here in D.C. (and Northern Virginia), commanders across the military services at the operational and tactical levels have been seeing the perils of our energy tether first hand, and have subsequently been voicing the need for real energy security alternatives that enable our warfighters in the field and support our strategic security interests. Just last week, a pointed letter penned by nine retired military “grey beards” was sent to the Senate Armed Services Committee reaffirming these harsh realities and supporting the military’s alternative fuel efforts.

The National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA)’s June edition of National Defense magazine also had much to say recently about balancing national security and lean times as well as about staying the course on strategic energy security.

In that issue, NDIA President Lt. Gen (Ret.) Lawrence Farrell, Jr., not only discusses the budgetary necessity to overhaul defense acquisition but strongly makes the case for continued defense pursuit of energy security and renewable technologies. A recent post by Andy Bochman at the well-regarded DoD Energy Blog focused in on Lt. Gen. Farrell’s emphasis on importance of diversification and value of time.

I would add a third core issue as that of uncertainty, and its implications in cost and investment risk. Pre-commercial technologies demo procurements always arrive on the market as quite expensive—our kids might not believe it, but I’m pretty sure Intel’s first batch of processors weren’t retailing for 100 bucks. Along those lines, fuel procurements on a per gallon basis come with a high price tag. That said, continual policy and market uncertainty will not serve taxpayers in saving their dollars, particularly in the long-run as the private sector equity factors these risks into the capital debt servicing prices.

|

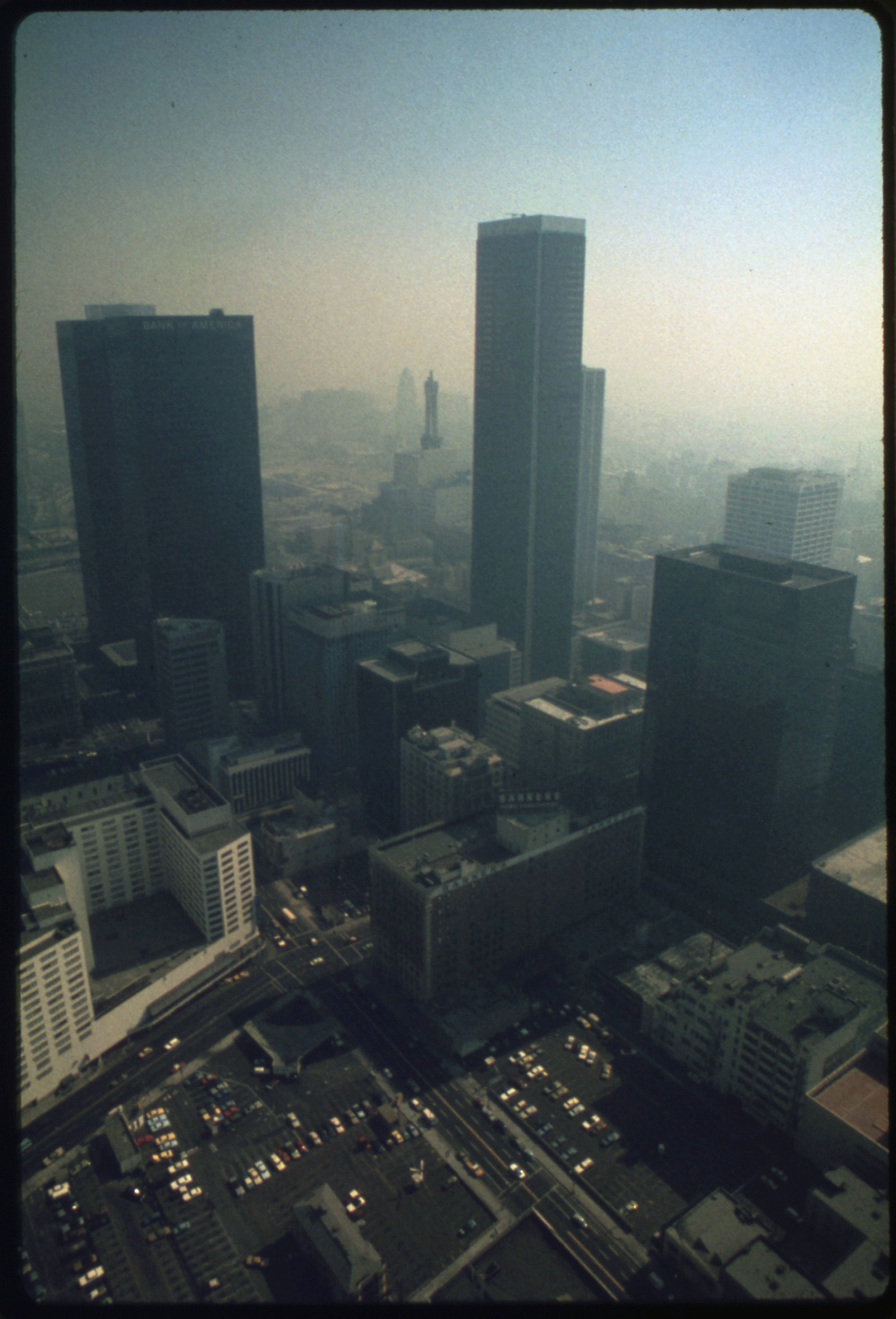

Expensive tastes.

|

But consider the situation at hand. Our defense capabilities rely on military JP-8/5 (jet fuel) and F-76 (diesel) fuels. Our tactical systems and weapons platforms represent trillions of dollars in defense investments and our warfighters can only fight if we have access to petroleum fuels (as an aside, the fully burdened cost of fuel is definitely not market spot price per gallon).

Military platforms cannot switch out to natural gas, wind, or other alternatives available to the civilian sector (except for aviation, which is likewise reliant on jet fuel). Many have said that DoD “would have access to the last barrel of fuel,” but at what cost to the remaining budgets for defense acquisition and training? More U.S. petroleum production helps, but only marginally so; this commodity is priced according to a volatile international market, which has increasingly been whipsawing the Services’ budgets as seen in past years.

We need diversified fuel sources to sustain our capability and reduce our strategic vulnerability. In our book, I mentioned the military’s early alternative fuel work that focused on converting U.S. fossil fuels into synthetic fuels for the purposes of energy security. The passage of EISA Section 526 put restrictions on the DoD’s ability to purchase these fuels because of their GHG emissions. But new technologies have emerged since then, and now drop-in biofuels offer diverse feedstocks and operational fuel solutions (with the potential side benefit of lower emission and environmental impacts) that can be accelerated to commercialization thru DoD’s early adopter purchases and participation in the Defense Production Act to accelerate cost competitive availability. However, these efforts are underfire for cost comparison reasons when compared with mature industry fuel products. Our warfighters and citizen soldiers deserve diversified and secure fuel supplies buffered against the volatile petroleum markets. We need to balance our priorities among fuels, training, and platforms. While we may not face a future of “cold iron” sitting in our ports, what is the effect on readiness and training at $125, $150 or $200 per barrel?

In contemplating the political... err, sensitivity caused of late by the military’s alternative fuel efforts, my thoughts jumped back to recent a U.S. Citizenship swearing in ceremony in Fairfax, Va. As I listened to almost 800 new citizens pledge their oath of allegiance to our great nation, my mind wondered back to over a decade ago when I had made a similar oath, one familiar to every U.S. public official, civil servant, or military service member. Our promise…“to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Our Constitution’s preamble provides us fundamental common ground in our efforts to “provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

With this in mind, I propose we take a deep breath, get to work, make informed and tough choices, and ensure we can afford to sustain US military capability and power past $125, $150, and $200 per barrel petroleum. We can do so taking a page from our 401(k) accounts…get up to speed, diversify, and rebalancing our portfolio constantly to maximize performance while managing risk.

I’m heading to NDIA’s E2S2 conference next week, and I hope to weigh in with some of the industry scuttlebutt. Hopefully, that post will include more on weapons platform comparison to conventional and alternative fuels, as well as observations from the ground at the conference.

+(2)+%5BRead-Only%5D.jpg)