The dog days of summer seemed to start a bit early this year. With fresh memories of “super derecho,” DC metro blackout, and lack of A/C in sweltering heat, I found myself enjoying some well-deserved leave time in Eastern Europe despite some unusually warm weather there as well. The good news is that there were no massive blackouts due to A/C loads, but the bad news is that there really wasn’t any A/C to speak of in the village. However, India didn’t have the same luck, with its residents, business, and economy enduring the “worst blackout in India’s history.” Reports of the transportation snarls, banking disruptions, and doubt over economic prospects seemed to surface rapidly. Returning last week, the news of US drought, call for disaster relief, and prospects of higher food prices seems to reinforce the universal lesson that brutal weather and climate impacts can have both very personal and national economic implications.

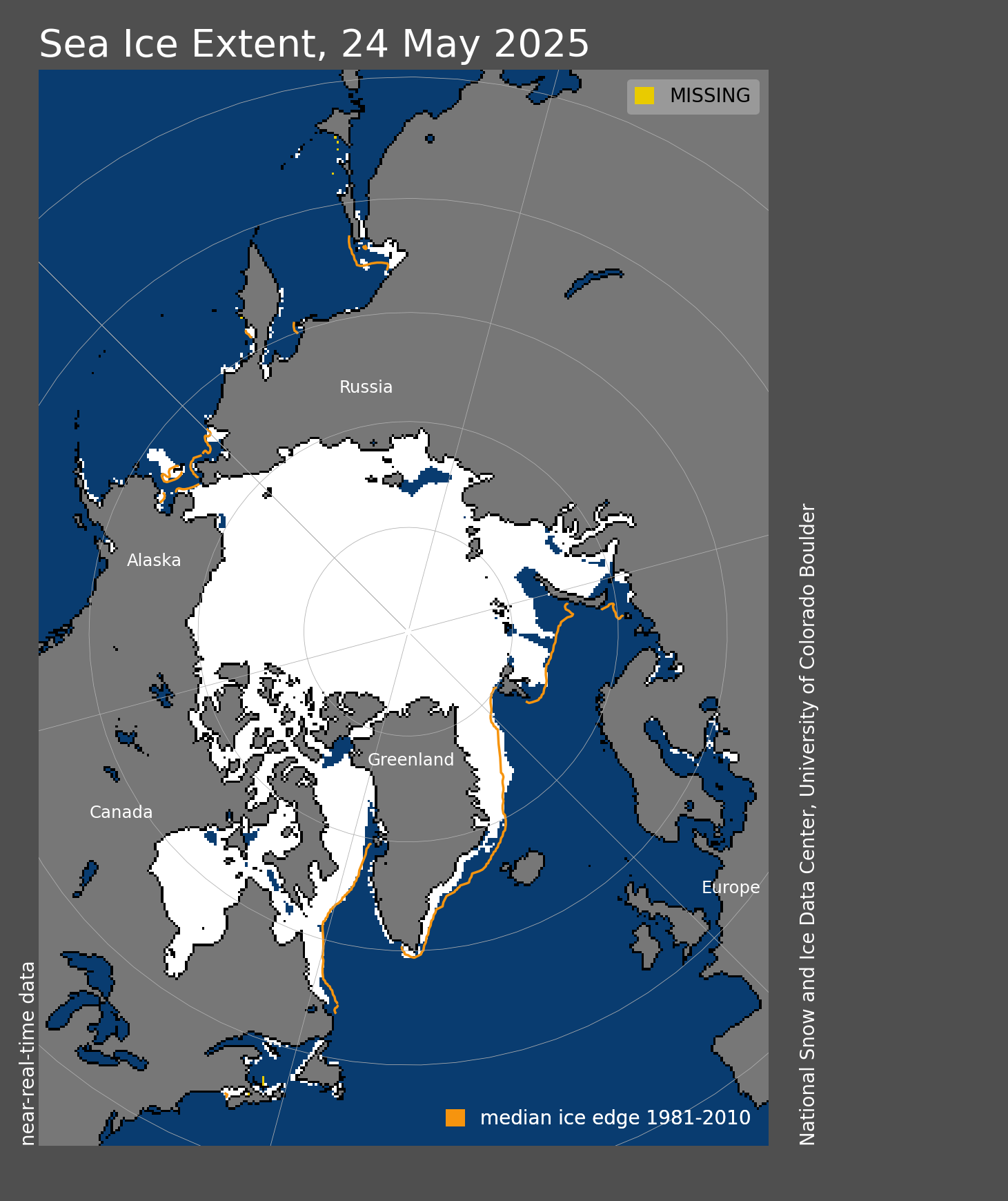

While many of us in the lower to middle latitudes are just trying to stay cool, keep the power on, and calculating corn futures, the Arctic ice pack extent numbers seem to be on track for record year, smaller than even 2007’s record.

|

Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

|

This summer’s season’s record ice melt seems to validate the Navy’s call to develop their Arctic Road Map and war game the national security implications emerging from greater Arctic access. Earlier this March, the Naval War College (NWC) released the findings report from the multinational Fleet Arctic Operations Game (FAOG), which held last September. Prior to its release, Admiral Jonathan Greenert, Chief of Naval Operations, suggested that the war game emphasized the need for international maritime cooperation. However, just this week, the NWCs’ Weekly Maritime News Survey referred readers current articles discussing Russian and Chinese interests in the Arctic.

If the FAOG war game enhanced multilateral collaboration, recent discussions on the Air-Sea Battle (ASB) framework have certainly not enhanced our mil-to-mil relationships with the Chinese military. While this reported ASB scenario focuses on a hot conflict with China, the DoD’s Office of Net Assessment's model may hold promise to help inform the capabilities need for the Arctic operational needs identified in the FAOG war game. These professionals are paid to think through the worst case scenario so our military services can make the case for balanced capabilities that can mitigate the impact of low probability, high-consequence security risks.

In my chapter on Climate and National Security, I’d emphasized the need to use scenarios and war gaming to not only think about a changing climate’s known unknowns but supporting our national security professionals in identifying the needed capabilities, gaps, and solutions, such as multilateral collaboration with our arctic allies (and competitors) who have those assets. Incorporating climate implications into our national security scenarios and war games is timely and needed to think about the threats of a 21st Century future security environment.

|

| Credit: DiGirolamo, SSAI/NASA GSFC and Allen, NASA Earth Observatory |

For example, a friend sent me an article during my leave about the rapid melt event in Greenland during the second week in July.

While current science can’t definitively tell you whether this rapid melt was a result of 150-year cycle, climate change, or some combination of both, the implication is that our military scenario makers can use such phenomena as inspiration, particularly when considering “worst-case” scenarios. As with the Arctic, war games focused on mild (0.5-meter sea level rise), moderate, or worst-case (7-meters) Greenland ice sheet melt can be valuable in thinking through the enormous national security implications, needs, capabilities, and gaps from such sea level rises. Regardless of nature of the threat, our military’s planning and preparing for the worst is job one.

Once we’ve done that, it brings us to early warning systems but that is a post for another day.

No comments:

Post a Comment