It’s a spooky time of year, but

I can’t help but be distracted by the climate change issue, even as costumes

and candy take center stage. It’s that there’s something about the theatrics

involved that remind me what’s at stake regarding the climate change issue.

Some background - I love

Halloween and was pleasantly surprised at our first Halloween in our

neighborhood when about six score ghosts and goblins, witches, princesses, and

supermen descended on our house cackling ‘trick or treat.’ So it’s fun to

prepare the house, dress in costume, and set the stage with pumpkins and all

sorts of ghoulish decorations.

Something that always gets kids

excited is the low billowing smoky fog that descends along the sidewalk from

the dry ice we hide in bushes by the door. Oh dear does that get them in the

bewitched mood!

And of course for the scientist

and professor in me, it’s great fun hearing the young ones trying to figure it

all out and answering their questions.

No, it’s not from a machine. It’s

not a ghost. No, the house isn’t really haunted. Yes, it looks like regular ice

but don’t touch!

And long about 9am, when the

smallest are already home in bed, the teenage goblins come a callin’. Then we

get into the serious questioning.

Why does it keep so low to the

ground [the very question reminds me of T.S. Elliot and the fog that “seeing

that it was a soft October night, Curled once about the house,

and fell asleep.”]. Well, I just have to explain the molecular weight of CO2

compared to the nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the air. Which goes a long way

to putting them to sleep. Or I could just say, well it’s heavier than air so it

gathers in the lowest places. It will even make pools in hollows if you watch

closely.

But it’s usually the more timid

schoolchild that asks ‘will it hurt me?’ Oh, that one really tears at my heart.

Does she mean directly, and now? Or is she asking me about a couple of decades

from now as we continue to add more and more to the atmosphere?

I could give the answer

OSHA gives … only if it exceeds 5000 ppm. In that case it’s a ‘simple

asphyxiant’ that affects the lungs, skin, and central nervous system with

symptoms like headaches, dizziness, restlessness, paresthesis; dyspnea;

sweating; malaise; increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, pulse

pressure; coma; asphyxia; convulsions. None of these are particularly

appealing. Let’s not go there.

Why do we so frequently hear

that CO2 is necessary for life and can’t harm you? Well, 5000 ppm is

pretty high and only occurs when you have a concentrated source of CO2,

either an industrial source or a natural one (a tragic example occurred at Lake

Nyasa in Cameroon and killed several thousand people in 2009).

But we don’t have to worry about

that. Do we?

Recently, as part of a

monitoring system designed to help the city track major sources of CO2,

the city of San Francisco installed sensors for CO2 on school

rooftops. The program has only been running for a few months but some data are

now available. You

might be surprised to learn that the highest recorded value is 1166 ppm.

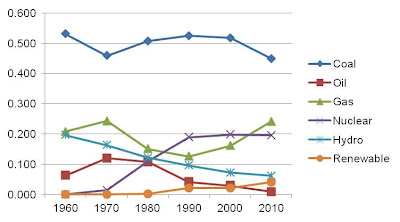

Remember, globally averaged CO2

levels have been rising rapidly but still only reach about 390 ppm. How does it

get to so large a value?

Well, if you are near a

concentrated continuous source the gas will not have dispersed by the time it

wafts past your school (or home, or workplace). There’s an interesting study (Project Vulcan) done by Kevin Gurney

and his colleagues at Arizona State University that shows the many large

sources of CO2 in the US and how the gas is concentrated far above

those average values over a large region surrounding the source.

|

| Los Angeles' visible effects of a CO2 dome |

So I think about her question,

‘will it hurt me?’ If the concentration of CO2 in cities already

reaches levels above 1100 ppm now, when the average is 390 ppm, what might it

reach if the global average CO2 level continues to rise, as it has

been rising at about 2% per

year, and reaches the global average 1000 ppm as assumed in the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change scenario

A1FI?

How about the long-term effects

of elevated levels of CO2 on children, or the old, or sick, or

pregnant women? Do we know what those may be? Do we know what we’re in for? For

example, the ‘acid-base imbalance’ noted by government

scientists, what will that do to my bone density?

So I can only look into her

questioning face, the little princess before me, and hope we don’t get there. I

hope she has a Happy Halloween. I hope we all give her treats, not dirty

tricks, in this scary new world she faces with a strange and chilling fog

swirling around us.